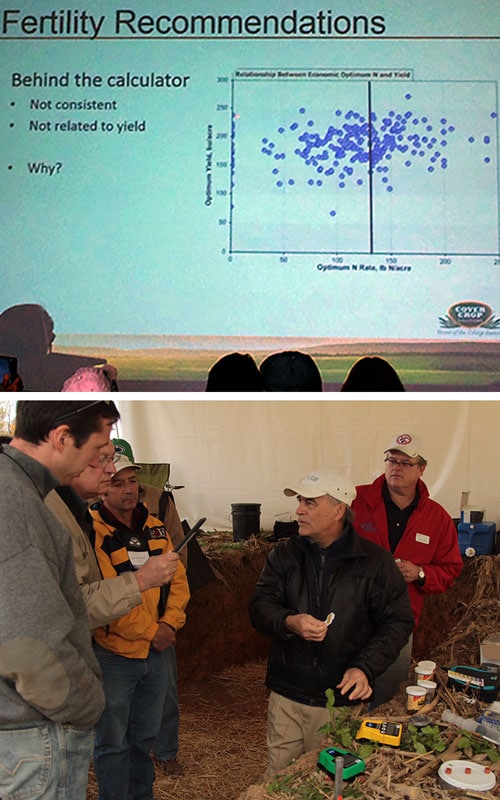

(Top) A nitrogen calibration graph by Dr. Blackmer shows the wide spread of possible yield response to added N. (Middle) Farmers gather to visit cover crop research plots at Groff’s Farm; (Bottom) PA crop consultants talk with Brinton (Woods End) and Chibirka (NRCS) about soil biology testing

Virtually all modern crop response studies trace their lineage way back to Liebig and Mitscherlich models. Liebig gave us the most limiting nutrient concept, often illustrated by staves of a barrel – considered a huge breakthrough at the time. Unfortunately, Liebig also insisted growers ignore any contributions from soil organic matter, conveniently helping spawn a century of over-reliance on manufactured nutrients (Liebig tried unsuccessfully to launch a patented fertilizer). Mitscherlich came along and refined Liebig’s inorganic model with the Relative Yield concept. This taught us the law of diminishing returns: as you approach maximal yield, less and less nutrients are helpful. It’s a thrifty model, and modern soil labs still use it to infer how much – or how little – fertilizer you should apply based on soil test results.

In science, models like paradigms do not work forever. Observations from the field in the emerging cover crop/soil health movement suggest that nutrient response models are awkward at best, and worse may not be working at all. Yet, soil test recommendations are still based on them.

At the recent cover crops field day (Oct 2014) at Steve Groff’s farm in Holtwood Pennsylvania, Dr. Tracy Blackmer (Cover Crops Solutions researcher) put up a slide (see chart) revealing just how poor these nutrient correlations can be: corn attained maximum yield at anywhere from none (0) to 250 lbs/N/acre. Soil Health Tool test results from across America are illustrating this result by accounting also for organic nutrient sources and CO2 respiration: some soils have huge natural reserves and the potential to supply even more nutrients naturally, and some have excess inorganic N from the previous fertilization – all contribute to “messing up” the yield response calibration – in other words, suggesting a lot less nutrients are needed than supposed. According to Dr Brinton of Woods End Lab who also spoke at the PA event, “Modern soil labs are not equipped to deal with this soil test crisis – many do no research, while University funds for research on nutrient calibrations are at an all-time low just when nutrient runoff and water contamination challenges are at an all time high”.

Where is all this leading? In the best of worlds, soil labs will work more closely on a one-on-one basis with growers while implementing new soil methods (like Solvita soil biology tests) to help better explain and “re-calibrate” crop results. Precision soil testing may help if it’s not designed to simply sell fertilizers. Many now believe that if we keep doing what we’ve done in the past- fertilizing based on outdated nutrient models – we are spinning our wheels at the expense of the farmer’s wallet and to the detriment of the environment.